Sytze Roos: A roving weaver

Like some modern-day roving journeyman he wanders from job to job, from experience to experience, seeking his challenges in a closeness captured with a spatial distance all his own. His life and work unfold between geographical poles in various parts of Europe. Quietly wandering and weaving, now here, now there, appearing at workshops, at symposia and at exhibitions. Present in the situation – but constantly on the move.

Sytze Roos has woven for more than quarter of a century. He had his first training at the cultic site Sätergläntan in Sweden, where the people of the crafts, from handicrafts to trade guilds, met and still meet in dialogue about the very fact of being part of a cultural landscape that is wholly dependent on relevant meeting and learning places. With his own craft Sytze Roos has explored his limits – human, textile and artistic. Irrespective of the passing waves of fashion and style – trends and snobberies – that have drawn the contours of the textile idiom in his time, he has intuitively chosen to follow a particular path.

The elements are concrete enough: craftsmanship extended by technology; influences from international textile art, where weaving and fibres were seen as opposed for a period, only to be reunited in new ways; a steady shift from craft to design and thus increasing curiosity about the ability to see perspectives in an ever more flexible theoretical framework. Practice and theory as opposites and as dialectically related in their own necessary spiral. Time caught up with him again – after a few years when teaching had taken over at the expense of necessary experimentation. Economics has its imperatives. But it also gave him the opportunity to pass on his textile legacy, at Sätergläntan as in other places.

Quietly he built up an awareness that he must search for something more than craftsmanship and the culture-borne tradition within a single area. Slowly, by inscrutable paths, the contours of a spiritual brotherhood emerged. Kasimir Malevich formed a starting-point. Three fixed points of reference made good sense in terms of the studies to which Sytze Roos himself turned: the influence of an original peasant culture, stringency in the use of colours and the exploration of a rigorous constructivism softened by the textile material.

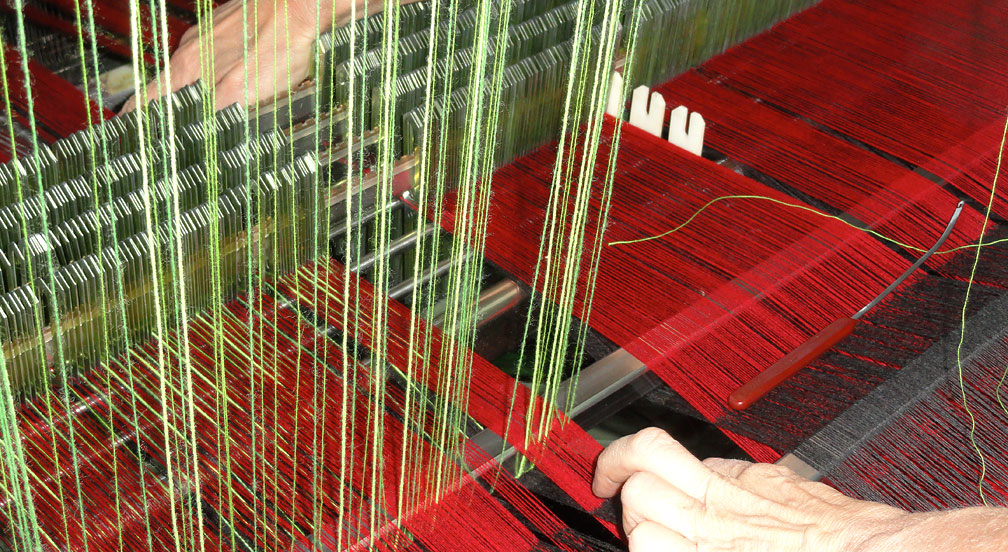

This was not a simple exploration, judged in traditional terms – rather an interest in how one can develop one’s own work so that it is kept within a clear framework, and at the same time is challenged and developed over time. Sytze Roos works both with extremely concrete, close things – woven cloth, collections at the international level and constant ‘product development’; but he does more than that. He establishes the ambience for his work: the tactile quality, the composition in every single sample, the very fact that he insists on continuing to weave. Think how tempting it would be to transfer the geometrical stringency to a canvas or absorbent printed sheet! And how much easier it would be if he could get around the petty aspects of the craft – the failures of understanding, the constant demand for marketability and continued production – by changing his medium. But no great doubts ever arise: as Malevich chose canvas, Sytze Roos again and again chooses his weaving.

Among the other models to which he relates his work, we find Piet Mondrian. Like Malevich, he too chose increasingly to relate to the three primary colours yellow, blue and red, brought into play between the poles of black and white. This set of norms is maintained, there is stringency and clarity; but the delimitation entails no real limitations – on the contrary. Within these bounds it is always possible to shift boundaries and create the new on one’s own premises. And it is interesting to see how one medium brings new energy to another.

If we pursue the paths described, the question naturally arises of the need for a kind of revolt – perhaps with a quiet touch of the courage to acknowledge one’s membership of a kind of anarchistic avant-garde – alongside the unwritten rules for working in the textile field. For is this not what Sytze Roos has done by insisting on his distinctiveness – by running counter to the beaten track and making precise, stubborn demands on his own capacity in his whole life and mode of living? He wills his works into being – on his own terms – and with that awareness he has long since crossed the boundaries of restrictive normativity. It is now something else that is in demand. Generosity of spirit, perhaps ...

By an incredible convergence of coincidences, Sytze Roos has come to resemble the Danish artist, art historian and provocateur Jens Jørgen Thorsen. Like the other artists mentioned in this context, he appeared throughout his life in several arenas. Important in this respect is the need to see, and to have the courage to create connections across the usual norms and understandings – textile as well as artistic. Against the background of the thinking that Asger Jorn and Thorsen developed almost half a century ago, summed up by the concept ‘Bauhaus-Situationiste’, Sytze Roos has identified yet another valid platform for his life and work right now and in the time to come. A life’s work cannot stand alone – the ideas surrounding it must necessarily be played off against a practice that is reflected philosophically and spiritually – that is why it makes sense to see every single visible product as a mirror-image of constant investigation – woven, painted or written.

Lisbeth Tolstrup

Textile designer and art historian

Member of AICA – Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) was preoccupied at an early stage with religious and philosophical questions. He taught at the same time as he attended courses in drawing and painting. At first he painted landscapes inspired by the area around Amsterdam and was influenced by the Hague school’s realistic-romantic attitude. Mondrian searched for a visual idiom that could capture spiritual and cosmic purity. He joined the Theosophy movement around 1909 and worked to simplify colour harmonies through reduction to red, blue and yellow. In 1912 he went to Paris, where he became interested in Cubism’s exploration of basic geometric forms. He came closer and closer to a geometric, abstract formal idiom – the essential structures. In 1917 he helped to form the group De Stijl with Theo van Doesburg.

Kasimir Malevich (1878-1935) passed through several of the stylistic currents of his time and is regarded as an important member of the Moscow avant-garde. He adopted subjects from Russian folk art and peasant culture to channel energy into his own works. He aspired to a constant simplification of form and questioned the obligation of painting to reproduce the real world. Around 1914-15 he created the picture Black Square, which is regarded a visual manifesto for the artistic school with which he is often linked, and which is called Suprematism. He worked with basic geometric forms in yellow, red and blue, as well as black on a white ground and the interaction between construction and abstraction. At one point he painted a white subject on a white ground – the ‘degree zero’ of form.

Jens Jørgen Thorsen (1932-2000) made his debut as a painter at the Artists’ Easter Exhibition in Copenhagen in 1949. Studied art history while developing his own art, which became more and more expressive and colourful. He never settled down in any one place and constantly provoked the bourgeoisie with his attitudes and political/ humorous happenings. In 1960-61 he was a co-founder of Bauhaus-Situationiste in Denmark along with Jørgen Nash, after Asger Jorn had been involved in the establishment of the international group. Their aims included the creation of new art forms and the transcendence of personal and artistic boundaries by means of actions, experiments, manifestos and films. The group ceased to exist around 1972.